No photos of me reading in South America, so here’s one of me reading “The Poisonwood Bible” while waiting for our flight to Kenya from Tanzania.

As a little girl, it often happened that my parents would suddenly realize I wasn’t behind them and look anxiously around, only to watch bemusedly as I crossed a busy street with my face partially covered with a book. I hid my own books (which varied from Goosebumps to Roald Dahl to books of poetry) in textbooks or open under my desk at school, so that formal education wouldn’t interfere with my own literary one. As a teenager, one of the biggest beefs I had with my stepmother was our inability to see eye to eye on whether or not it was acceptable to read throughout dinner, regardless of whether we were at home or at a restaurant. As a freshman moving into my first dorm, I brought with me more books than clothes. As an adult, my friends consider me a lending library without late fees. From the day I wrenched Go, Dogs, Go! out of my father’s hands to read it myself till now, books have been one of my main connections to the world outside my little insulated piece of it. A look inside my head would reveal that I carry with me the characters of books I’m reading, the words of authors I’ve loved, the stories that have had some kind of impact on me. The words of others have always had the power to anchor me to the present, entice me back into the murkiness of my own memories, or vault me into a barely imagined future.

There are many, many things I love about reading but one of the most interesting is how someone else’s story, whether real or imagined, can help you understand your own personal experiences in rich and unexpected ways. Before I ever set foot on a plane or in a foreign country, books were my passage to worlds I had never imagined, lives I could not have related to beforehand, ways of thinking that pushed up against mine like an opposing magnet. Now that I’ve actually been to different parts of the world, certain books have allowed me to delve deeper into whatever country or culture I found myself observing and, hopefully, participating in. The first time I truly felt this was when I read Ngugi wa’ Thiongo’s novel Petals of Blood* whilst on safari in Kenya, which is where the book is set. On the same trip, I also read Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, and I felt my heart break as it opened itself up to a new and painful understanding of the White Man’s parasitic influence and history in Africa. Since I’ve been in South America, I’ve made a point of trying to read books that I felt would add some depth to my travels and I can’t believe the poignancy and absolute fucking perfection of some of the books I’ve read paired with the moments, places, and frames of mind in which I’ve read them.

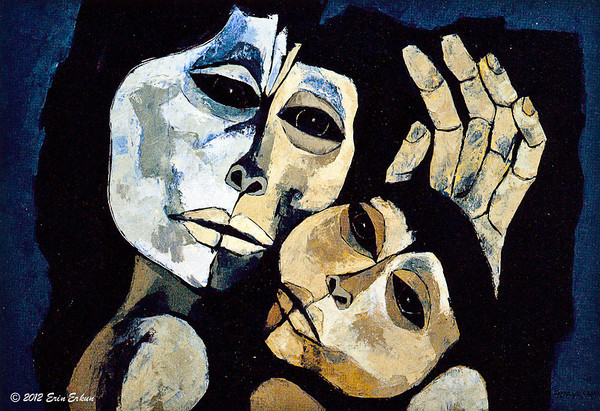

I think it is a good idea to know a little history about the country you’ll be visiting, to be an informed tourist. It gives you context, a frame of reference. It helps you understand the whys and hows and WTFs that so often accompany traveling to new places. For this reason I decided to read Eduardo Galeano’s Memory of Fire trilogy, a history of the Americas that arcs from the creation myths of the ancient civilizations to the conquest (in Genesis) to independence (in Faces and Masks) to nationalization and the civil wars and military dictatorships of the 20th century (in Century of the Wind). It is written in a way that appeals to the fiction reader who does not usually pick history books off the shelf. Instead of the dry and lengthy texts one usually expects, Galeano tells this particular history in the form of short “stories” or anecdotes, usually no more than a page or two long. Each one concerns an event, idea, or person that makes up the patchwork of Latin American history.

His words and images came to me often: while visiting the Museo de Oro* in Bogotá, for example, or while picking my way through volcanic rocks to La Lobería on San Cristóbal, or most devastatingly in the Guayasamín* museum in Quito. It made each place I visited seem like more than just a static place in time, one place in one moment in which I (one person) was visiting. Suddenly it was like I was standing in one place, the present, while being given the gift of simultaneously looking behind me into the past. These were histories I had never heard of. Genocides and triumphs, violations and acts of heroism that were suppressed in the institutionalized practice of omission and hypocrisy that is grade school American History. Sometimes I would get so angry reading these accounts that I would have to close the book, feeling ashamed of the lengths to which my country has gone in order to secure its own success at the expense of others (mainly South and Central America). But that is exactly why I read. I want to know things that pain me so that I can better understand and empathize with the reality of the people I meet and the places I travel to. In this case, ignorance is not bliss, but blatant irresponsibility.

While reading this trilogy (which is wonderful and I recommend it, though it is not exactly a page-turner), I began to read other books that had been sitting on my reading lists for who knows how long. Possibly the most important of the whole trip was Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. This is Strayed’s account of her own solo three-month hike on the Pacific Coast Trail, which stretches across the coastal United States, from Northern Mexico to Canada. I picked it up because I had read some essays of Cheryl’s, but I was not in any way prepared for how much it would resonate with me. Despite the fact that the impetus for her journey was to find some escape and relief from the traumas of death, divorce, and addiction while mine was only to escape ennui and days spent in a job I despised, it was the fact that we were both women traveling alone, searching for something we could not define, that spoke to me.

Sometimes I would be reading and it would be as if her words had torn themselves away from their embryonic siamese twin in my head. At other times her words of strength and resilience and power would come back to me in moments of anxiety, like some enchanted mantra designed to keep me from submitting to weakness.

Fear, to a great extent, is born of a story we tell ourselves, and so I chose to tell myself a different story from the one women are told. I decided I was safe. I was strong. I was brave. Nothing could vanquish me.

These words, Strayed’s words, forced themselves through a fog of worry as I sat at the back of a twenty-five cent colectivo full of rough-looking men which was supposedly heading to the Peruvian/Ecuadorean border. While having a minor panic attack 80 feet below the waves off the coast of the Galápagos island of San Cristóbal*, these words wrapped around me like a warm current (or like peeing in your wetsuit): “I only felt that in spite of all the things I’d done wrong, in getting myself here, I’d done right”, and my panic faded. When she spoke of how laughably ill-prepared she was for her trek, I could think only of my own lack of preparation when I started out on my hike through the Colombian jungle north of Santa Marta, in search of the Ciudad Perdida, with all the right gear and none of the necessary experience. Perhaps most importantly of all, it was in this book that I first read the poem* excerpt that I later tattooed on my shoulder in Cuenca:

When I had no roof, I made audacity my roof.

I have learned what Cheryl learned: while traveling alone, you find that you yourself are capable of so much more than you had ever imagined.

Into the Wild was a book I had been meaning to read for a very long time. I had seen the movie so I knew the gist of it: man v. wild; wild wins. But it was the main character, Christopher McCandless’, desire for freedom and the unknown that called me to read it while on my own travels. Although I admire much of what McCandless accomplished, I took this book as more of a warning than anything else. His story, though it also includes moments of the kind of transcendence and self-fulfillment that so many travel books do, is ultimately a reflection of the darker side of travel. So much of traveling is absolute wonder, but there are infinite opportunities for things to go wrong, sometimes fatally so.

Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the beginning think what may be the end.

This book reminded me that though I may feel free, I am not invulnerable to accident, to malice. I have a responsibility to do everything within my power to deny the “siren song of the void” and come back to the people who are waiting for me.

Reading allows you to live the lives of other people who have had similar experiences to yours, to learn from their mistakes and successes. For me, reading these and other books during this time has augmented my travels in a way I don’t believe anything else could have. There have been moments while reading, on a bus from here to there, on a bench on the malecón in San Cristóbal, while lying in a hammock with a Pilsener within reach, where I have laughed out loud to read something that so closely mirrored, explained, or otherwise encapsulated my own experiences. I don’t expect everyone to understand this post, to be able to relate. There are people to whom reading is akin to breathing or eating, there would be no life without it. It is to those people that I am writing this blog, although I hope everyone else will take something from it as well. But there is one thing that I think anyone can understand: reading the stories of others who have led or are leading similar lives to yours… it helps you feel less alone when the sheer size and force of the world seems just a little too overwhelming.

*Click these links to see the blog entries where they are discussed more in depth.