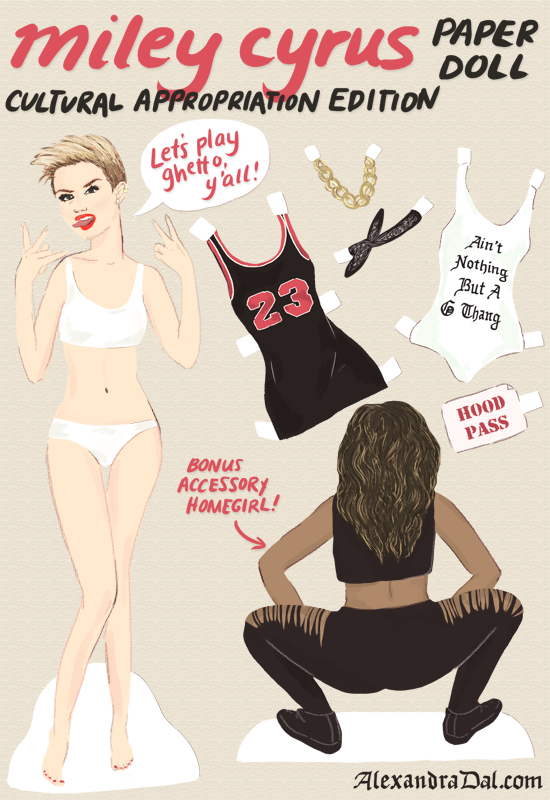

Cultural appropriation: the act of taking an image, tradition, or aesthetic from its cultural context and repurposing it in a way (generally as a style or decorative item) that has no ties to its original meaning within a cultural tradition. This is a term you may have heard a lot recently, especially in pop culture. Iggy Azalea is constantly under fire for being a white rapper who appropriates black style and sound, while Taylor Swift has gotten into trouble as a result of her new music video which seems to celebrate the glory days of white colonialism in Africa. Miley Cyrus, who many would highlight as the face of cultural appropriation, uses black women as stage props, “whitesplains” Nicki Minaj, and wears dreadlocks on national television. Cultural appropriation tends to be a sin of the dominant culture, the one historically most responsible for exploitation and colonialism — white culture.

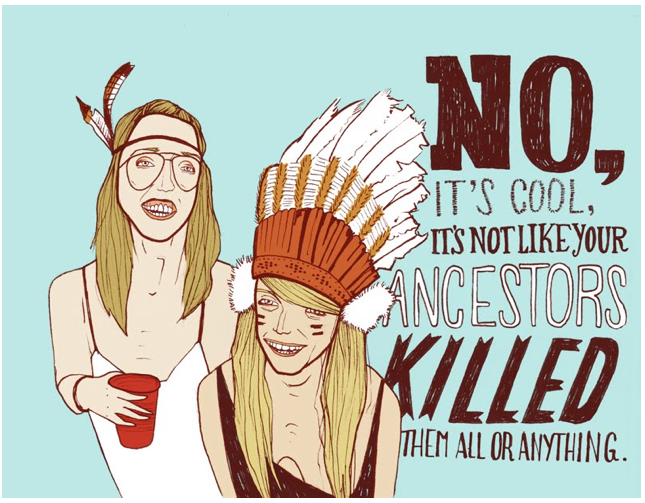

I have always felt cultural appropriation to be a highly problematic idea on both sides of the argument. On the side of those who feel appropriated, I can see why. White settlers decimated Native American populations in a genocide rarely called by its true name, and now young whites dress up in headdresses and warpaint for parties, football games, and music festivals. As certain tribes scalped their victims and displayed them as badges of courage, now we wear the symbols of those we virtually destroyed. After centuries of enslavement and debilitating enslavement in Africa, Urban Outfitters sells tribal prints at a premium price and TV personalities cornrow their hair. While presidential candidates build their platforms on the shameful dirt of mass deportation, costume companies make serious money off selling culturally insensitive costumes involving ponchos, sombreros, and stick-on mustaches and people get wasted on Cinco del Mayo. The argument against cultural appropriation is this: by choosing to wear symbols taken from systematically exploited cultures while remaining ignorant of the symbols’ value or meaning, we perpetuate violence. I can agree with that.

Photo Credit: SJ Wiki

However, there are certain oft-mentioned examples of cultural appropriation that I do have trouble getting on board with, the most obvious being dreadlock, cornrows, and braids. Black culture states that these hairstyles are traditionally black, necessary because of the unique texture of black hair. Understood. And yet I have a hard time believing that a hairstyle is a truly defensible part of any culture. Granted, the white person on whom cornrows or dreads look good is rare, and yet they also have hair, which may have a difficult texture or length to easily manage. While traveling South America, I’ve met many people with dreads, from Sweden and South Africa and Australia. Why? Because, aside from shaving one’s head, dreads are the easiest hairstyle to care for when showers are anything but guaranteed. Long hair in hot weather begs to be braided and put up, regardless of the skin color of the scalp it’s attached to. If the argument is that braids are intrinsically black, then what about the braided styles based in the cultures of indigenous America or the Alps or the cold northern lands of the ancient Vikings? We all have hair, so I don’t think anyone, regardless of culture, can copyright its style.

In the big heaving morass that is cultural appropriation, the real question for me is where the line is between appropriating someone’s culture and having the right (or privilege) to wear or otherwise display a cultural symbol. So it’s probably insensitive to buy bindis and tribal print dresses at Urban Outfitters, but what if you buy something directly from the culture, one that makes its living off of selling traditional jewelry or clothing to tourists? Is it wrong of them to sell it? Or only wrong of consumers to buy it? In Ecuador, the country I’ve been living in for a year now, the indigenous people of the northern town of Otavalo have become one of the most successful indigenous groups in the world because they have so effectively marketed their beautiful alpaca-wool hand-woven fabrics. I bought an insanely soft scarf to protect me from the Andean chill. If I wear it, am I wrongfully appropriating Otavaleño culture? When I was in Kenya, I bought an intricately beaded necklace from a Masai woman. Is the fact that it hangs on my wall a sign of my cultural insensitivity? I’ve spent most of my life learning Spanish, spent years living and traveling in Central and South America, immersing myself in their complex, wonderful cultures. Are my Mexican folk art-based tattoos an act of violence?

My views on cultural appropriation are an incipient snarl of thoughts and feelings which I have a really hard time sublimating into a coherent argument. Nonetheless, I am aware that I hold a position of immense privilege as a young, white woman, but even with this potential bias forever in the forefront of my mind, I can not reconcile my own beliefs with the far-reaching tenets of the arguments around cultural appropriation. But my goal with this post is not to take a side, not to say who is right and who is wrong, but rather to open into a discussion a topic that has long been pushed under the rug by the “guilty” party — white culture. While it’s common to hear celebrities get slammed for cultural appropriation, we rarely hear a thoughtful response from them or anyone else. An argument in which only one side is participating is not an argument but a diatribe, and a diatribe, while not necessarily lacking in validity, will not bring about change.